The Rise of Opinionated Blockchains

Permissionless VMs and programming new block validity conditions

Summary

The Appchain thesis has failed so far. Application specific chains have not lived up to expectations because of their complexity. And the few exceptions (perpetual DEX chains) are pivoting to platforms. But Appchain evangelists weren’t entirely wrong…

…Being able to program opinionated block validity conditions is the key feature that make appchains powerful. By allowing developers to define arbitrary conditions for what makes blocks (in)valid, apps can restrict validator misbehavior (e.g., MEV) on a per-block basis. Smart contracts on the other hand, can’t give essential per-block guarantees for time-sensitive functions.

Instead, opinionated Chains are emerging as an architecture which combines the best of Appchains (programmable block validity conditions) and Generalized Smart Contract Chains (an atomic, shared environment). They remove the complexity of cross-chain flows, but retain the ability to program opinionated block validity conditions to support critical applications.

Introduction

The Appchain thesis stated that applications would want to own as much of the stack as possible, driving them to leave their L1s and build app-specific chains. By controlling the whole stack, applications get more fine-grain control to solve critical problems which are out of reach for smart contracts.

But as until now, this appchain thesis has failed to materialize. Its proponents underestimated that:

Users are turned off by the cognitive overload fragmentation creates.

Financial mechanisms are held back by bridge latencies and non-atomicity.

Applications developers lose focus by dealing with the complexity of asynchronous flows and chain infrastructure instead of improving product.

In the wake of this, a promising middle ground between generalized and application-specific chains has emerged - Opinionated Blockchains. In this post, we discuss what Opinionated Blockchains are and the features that make them more effective : the ability to program new block validity conditions.

A Brief Intro to Opinionated Blockchains

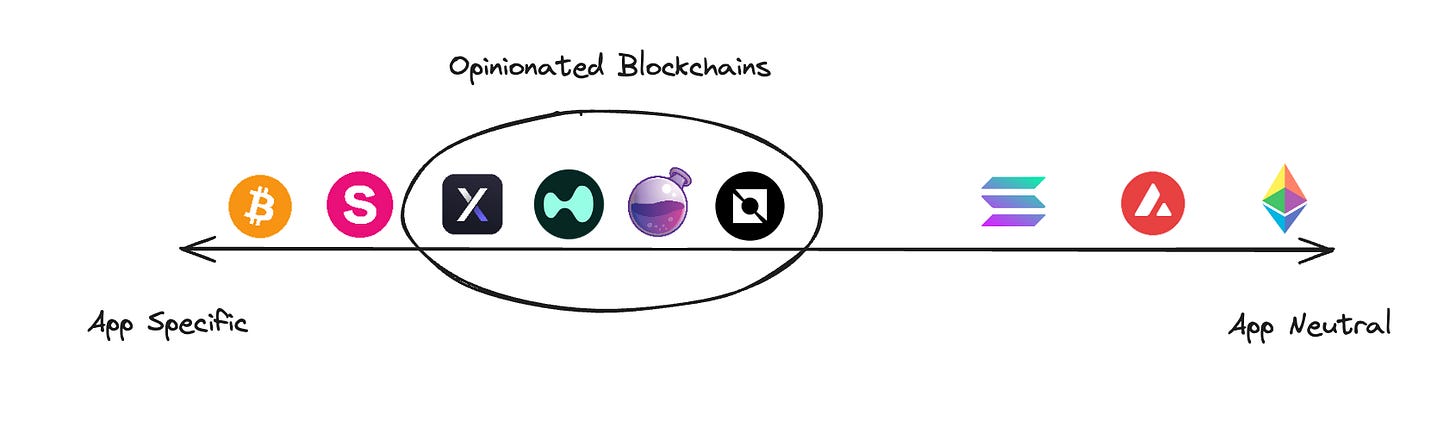

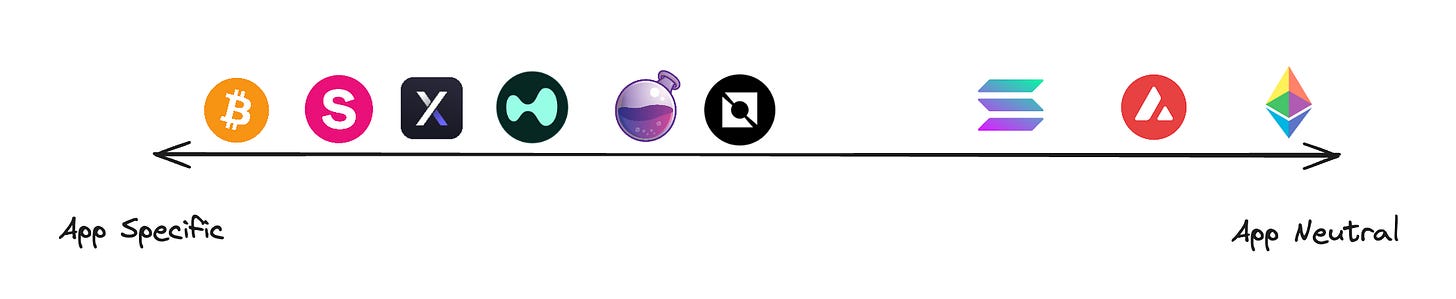

One dimension to define Opinionated Blockchains on is Application Specificity with respect to it’s developer ecosystem.

Generalized Blockchains and Credible Neutrality

On one extreme, you have Ethereum Mainnet, which actively seeks to be credibly neutral. This entails avoiding preferential treatment to any user or outcome. According to Vitalik, there are four rules for achieving this :

Don’t write specific people or specific outcomes into the mechanism

Open source and publicly verifiable execution

Keep it simple

Don’t change it too often

An implication is that there is no distinction between what is ‘infrastructure’ and what are ‘applications’ at the smart contract level. The protocol shouldn’t treat contracts differently whether they’re called in a contract-to-contract way (e.g., an oracle contract called by DeFi protocols) or a consumer-to-contract way (e.g., a memecoin trading platform called by end users).

Although Solana is more explicitly focused on DeFi, it’s not much different in this sense. Its product strategy largely revolves optimizing the speed, cost, and scalability of generalized infrastructure. Similar to Ethereum, all smart contracts on Solana rely on third parties for infrastructure like price oracles and keeper systems for automation.

This approach optimizes for a free marketplace of applications and infrastructure. Developers feel comfortable that the platform they are building on won’t pivot to internalize their value, increasing their willingness to place bets with their careers. It also minimizes the complexity of the core protocol. This reduces the surface area for critical bugs, supports the focus of the core development team, and makes it easier for node operators to participate.

However, as appchain disciples point out, it’s not without drawbacks. Notably, it limits expressivity (which we explore in the rest of this post). Another downside is that applications become reliant on trusted third parties (TTPs) for core infrastructure. The original promise of blockchains was trust-minimized financial systems. But what we have today looks much different - applications trust additional intermediaries for price feeds, block builders, keeper networks, cross-domain messaging and more.

Appchains

On the other extreme, you have single-purpose blockchains like Hyperliquid and DYDX which enshrine an application into the protocol. Their guiding principle is maximizing the quality of the enshrined application.

The attractiveness comes from the ability to control a greater breadth of functionality than what can be built on a smart contract. As we’ll discuss, this additional functionality can be used to solve critical problems and internalize more revenue.

However, the success of perpetual appchains (e.g., DYDX and Hyperliquid), is better thought of as the exception rather than the rule. There is a graveyard of dead or underperforming application-specific blockchains that haven’t failed because of a lack of interesting technology (look no further than the Cosmos ecosystem).

The reality is that managing an entire chain is tough, leaving many aspects of UX worse off : Users need to manage more accounts, developers need to manage more infrastructure, business development needs to coordinate more novel integrations, and asynchronous composability doesn’t afford the same financial guarantees for critical, time-sensitive actions like arbitrage and liquidations.

Roads Leading to Opinionated Blockchains

Some surviving appchains have responded by expanding scope due to an inability to capture market share on the fragmented experience of a single app. Although they started as a appchain, Osmosis (DEX) has launched a permissioned smart contracting layers to host additional, external applications (e.g., Levana’s Perpetuals DEX) that can strengthen their network effects. In doing so, friction for users is reduced, and mutualistic applications (e.g., Leverage ↔ Spot exchanges for safe liquidations and volume) can reenforce eachother.

And even for the pair of perpetual DEX chains that have performed well - Hyperliquid and DYDX - transitions to becoming developer platforms are in the works. Both have announced permissionless virtual machines (Hyperliquid’s tweet; DYDX’s founder’s tweet). Other than increasing the total addressable market, the motivation for product are the benefits of atomic composability. If a protocol wants to accept non-stablecoin collateral, they need to ensure liquidators can sell it quickly for a token liquidators want to hold. The strongest guarantee you can give liquidators is atomic access to deep spot liquidity (i.e., being on the same chain as a large spot DEX). By doing so, liquidations can happen in a self-financing, atomic way with flash loans. The efficiency of this helps to minimize the risk of bad debt for the perpetual DEX. Interdependencies (between yield, leverage and exchange) that benefit from atomic composability show up in many other places as well (e.g., atomic leverage looping or spot DEX arbitrage).

Teams previously behind smart contract applications are also choosing to build their next iterations as platforms. One example is Lido for the Interchain (→ Neutron). The reason for the transition was bottlenecks to product development, which could be mitigated through a shared ecosystem on an opinionated platform. Previous interchain liquid staking platforms relied on enshrined heavily on enshrined modules which were only accessible to chain developers (and not smart contracts). But isolating as an appchain didn’t make sense given how integral atomicity is to the use of LSTs. For example, a widely popular use of LSTs in DeFi is atomic leverage looping, where a user stakes to an LST, posts it as collateral, borrows more of the underlying, stakes to an LST, and repeats until it can’t borrow more. As a result, Neutron was built to expose smart contract hooks into enshrined modules for trust-minimized queries, account management and native automation. This allows interchain LSTs and other apps to be built on a shared environment as smart contracts instead of as entirely new, isolated appchains.

Programming Block Validity Conditions

A natural question to ask is what set of new functionality is enabled by making opinionated decisions about a blockchain’s design ?

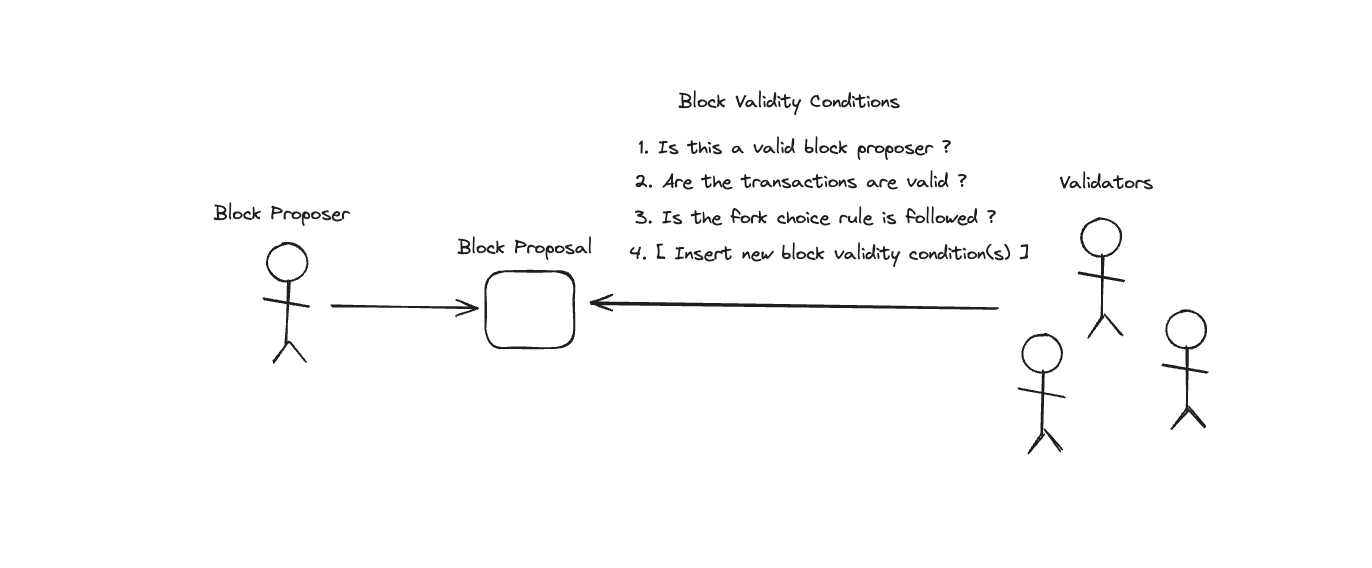

Greater expressivity concretely means the ability to program new block validity conditions.

Let’s dive into what this means in practice…

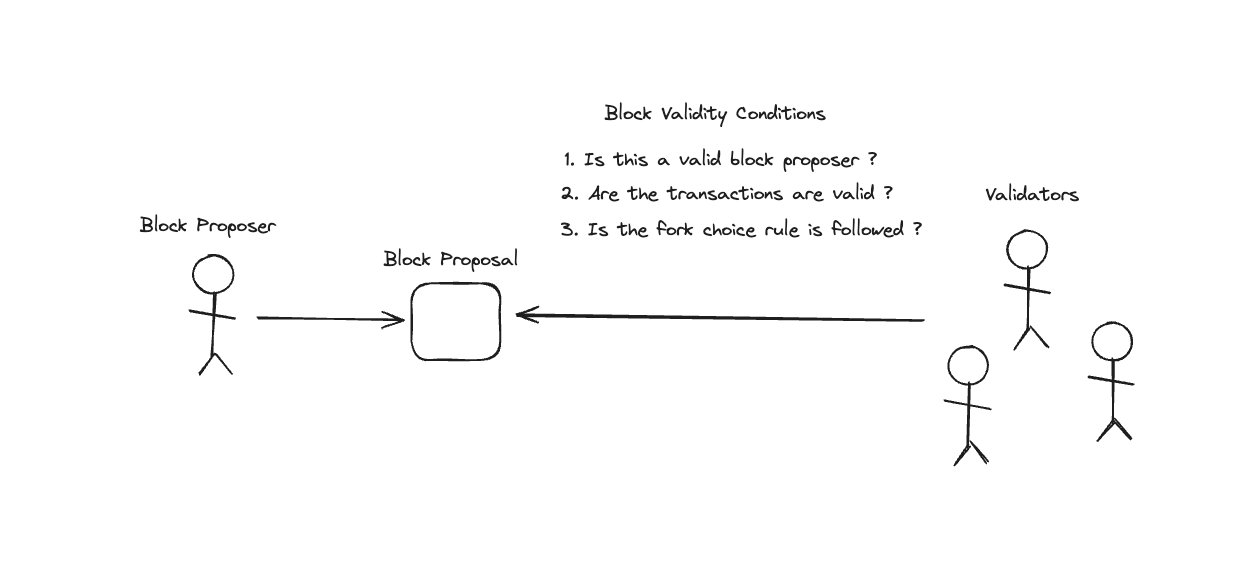

A typical blockchain today will have three validity conditions :

The block proposer is a valid leader (e.g., they found a valid hash for PoW or are next in line for PoS)

The proposed transactions are valid (e.g., the state transition function was properly executed for each transaction)

The fork choice rule indicates the proposed block is the new head of the chain (e.g., longest chain for PoW or sufficient votes for PoS)

If these conditions are met, the proposed block is accepted.

While there is no technical reason why existing blockchains can’t introduce additional validity conditions, there is good reason why they can not be made permissionlessly programmable. In the event that anyone could enforce new validity conditions, anyone could create arbitrarily difficult or conflicting ones that can’t be met.

But not having access to programming block validity conditions prohibits the design space for solving critical problems such as :

Trades being censored and reordered in extractive ways

Oracles (price feeds) being delayed and manipulated in extractive ways

Inefficient portfolio rebalancing leading to exorbitant losses

Delayed liquidations leading to protocol insolvency

Enshrining additional validity conditions opens up three tools for developers that can be used to mitigate these problems :

Per-block inclusion guarantees: many of the most important functions in DeFi are time-sensitive and would benefit from stronger inclusion guarantees. For example, adverse selection in market making from rebalancing or oracle delays, and insolvency due to delayed liquidations are both (in part) due to the inability to get specific transactions included in every block.

Socializing gas costs : the costs associated with fulfilling validity conditions can also be socialized across the entire network. For an oracle, this means that accurate, low-latency price feeds are available as a public good for smart contracts rather than a pay-to-play service.

Reducing reliance trusted-third parties : as previously mentioned, smart contracts on generalized platforms are reliant on a slew of additional committees for core infrastructure - for example, price feeds and keeper networks. By enshrining these functions as prerequisites for block validity, the trust can be moved to the same actors already being trusted for the chain’s liveness.

The underlying problem block validity rules can solve is that the block proposers responsible for including and ordering transactions have an incentive to deviate from the intentions of smart contract designers. When they deviate, not only do they still receive payment for proposing the block, but they also receive the profits from undermining user and application welfare. By defining additional validity conditions, states deemed critical, can be credibly met in every block. If the conditions are not met, the block will be deemed invalid, and no payment will be received by validators for their work.

To Enshrine or Not to Enshrine ?

To understand this better, we’ll explore the approaches that Generalized Blockchains and Opinionated Blockchains will take to weighing these tradeoffs. In doing so we’ll also get a better idea of what technically differentiates a “General” Blockchain, from an “Opinionated” one.

Choosing Validity Conditions for General Blockchains

While General Blockchains will avoid enshrining conditions which undermine their neutrality, they won’t just leave all the innovation to be captured by opinionated chains. Outstanding proposals (e.g., inclusion lists and blockspace futures) for generalized blockchains often introduce new block validity conditions. They avoid biasing the chain by only reserving blockspace for smart contracts through open competition. To understand this better, let’s discuss two examples.

Inclusion Lists : One mechanism for improving censorship resistance is to form a list of transactions that is collaboratively built by multiple validators’ views of the mempool. At the top of every block a check is done on whether a sufficient number of validators contributed transactions to the list AND that the valid transactions from the list were included in the block. Since the block would be invalid if these conditions were not met, the block proposer would have to forgo their block rewards in order to censor them. This is known as an inclusion list.

Although it involves enshrining new functionality, inclusion lists actually reenforce credible neutrality. They prevent block proposers from being able to discriminate between transactions for personal game by making it impossible to censor a transaction that meets certain conditions.

But it’s quite possible that there just isn’t enough space in a block for all the transactions that made it on the inclusion list. As a result, a mechanism for allocation is needed. And given their fairness and sybil resistance some kind of open auction is the likely choice.

Since there is a markets for inclusion are still involved, inclusion lists can not give certain per-block guarantees. There may be time-sensitive, socially useful services which can’t afford to bid for inclusion in every block. A price oracle which tries to post price feeds for every asset, would be too expensive to pay for every block, especially during periods of congestion. But if it were done, automated market makers and lending facilities and could reduce their risks and costs. This resembles a tragedy of the commons (coordination failure), where most useful protocols and players would benefit greatly but coordinating a fund which does this is practically impossible.

Blockspace Futures : Over the years, designs for blockspace futures have been explored at length. Similar to inclusion lists, these designs involve an open market and an additional check that purchased blockspace is honored.

Unlike standard transactions which are immediately executed, blockspace futures allow users to reserve execution at a specific point later on. This might be useful for financial reasons such as hedging (e.g., a validator could short a blockspace to lock in predictable profits during a volatile period), but it could be useful for enhancing applications. For example, many applications rely on third-party keeper systems for automation. Keeper systems can be unreliable as they are subject to censorship or congestion during sensitive tasks. In theory, applications could replace keeper systems by purchasing blockspace futures that guarantee the execution of sensitive tasks ahead of time. But how practical this would be largely depends on the pricing of blockspace futures market - if the futures markets become too expensive, you’d have the same problems as without them.

Choosing Validity Conditions on Opinionated Blockchains

This brings us to what opinionated Blockchains can do that generalized ones can’t. In both examples we explored - blockspace futures and inclusion lists - market based participation makes it impossible to reserve resources for specific transactions.

But there are still incredibly important functions (e.g., oracles or keeper systems) that are most effective when done at high-frequencies. In practice, these functions are unreliable due to their costs and the incentives to game their inclusion. By giving these functions per-block guarantees as opposed to “whatever can be afforded in a given moment” users and applications can take on less risk and capture better margins.

Notably, the transactions which can pay the most for inclusion, are often the least socially useful. This is because the more extractive a transaction is, the more it can afford to redirect some of that extraction to a block proposer.

To see what can be accomplished by enshrining more opinionated block validity conditions, let’s explore some notable examples and contrast them to their unopinionated counterparts.

Inclusion Lists → Enshrined Oracles: oracles serve critical functions throughout DeFi - many borrow lend protocols, and perpetual DEXs rely on them for monitoring solvency and pricing trades. However, protocols today rely on third-party oracles subject to validator and searcher profiteering from transaction fees, censorship and ordering manipulation for time and order-sensitive price feeds.

Fundamentally, the problem of designing an accurate oracle is one of consensus - how can a set of participants agree on some value? This makes it fairly natural for opinionated blockchains to enshrine oracles as part of the consensus process. In addition to their votes on block validity, validators can be required to submit various price feeds. If a sufficient number of price feeds are not included (e.g., this could be the same threshold needed for block validity), then the block as a whole is deemed invalid.

This is roughly the same mechanism as inclusion lists in that a sufficient number of contributions need to be aggregated from each validators in order for the block to be valid. The primary difference being that inclusion for enshrined oracles is not market-based as blockspace is reserved for the specific task of publishing price feeds every block.

By guaranteeing price feeds are available at the top of every block without additional trusted third parties, a chain can stop oracle manipulation for profit (e.g., censorship and ordering manipulation). Fresher oracle prices allow for less adverse selection and faster liquidations, reducing the risks for on-chain market makers and lenders.

This also socialize the costs of publishing price feeds. Instead of a pay-per-query model where applications need to trust a third-party and pay an additional service fee, high-fidelity price feeds become a public good with fewer trust assumptions.

Blockspace Futures → Enshrined Keeper Systems :

While they would potentially be better than today’s keeper systems, there are still problems with using blockspace futures markets for reliable automation. For one, they don’t exist in production for in-demand chains. But if they did, similar to spot blockspace pricing, futures markets could see erratic pricing in the face of congestion.

In light of no blockspace futures market, smart contracts rely on incentivizing imperfect third-party keeper systems. These are off-chain actors who are rewarded for triggering functionality on a smart contract. If the incentives are not enough to outweigh transaction costs or profit can be made from censoring or manipulating the keepers’ transactions, the system will not work as intended.

Opinionated blockchains can enshrine these keeper systems as validity condition to improve their reliability and internalize the profits. As a result, critical functions could leverage the three advantages mentioned earlier : per-block inclusion and socialized gas costs.

One useful example could involve a mitigation of Loss Versus Rebalancing and Impermanent Loss. This is perhaps the most pressing problem in all of DeFi. Each of these terms points to the losses that market makers face to arbitrageurs due in part to the limitations of market design on generalized blockchains. Opinionated blockchains can offer unique solutions, not possible elsewhere. For example, automated market making strategies can be given priority every block to cancel and place orders on a shared orderbook. In doing so they can minimize the value leaked to arbitrageurs or even capture the arbitrages itself.

Giving vaults structural advantages opens up a new design space where passive strategies can perform just as well or better than sophisticated players, but with a much larger capital pool to pull from. This is because sidelined capital which was previously incapable of running sophisticated strategies can now get access to automated, high-frequency market making on fresh prices. These would look similar to HLP vaults, but entirely on-chain and generalized to any type of market (e.g., spot, futures, options, borrow-lend).

There are some tradeoffs worth discussing. Introducing new conditions can also inhibit competition between users. Consider a DEX which enshrines a vault that is given priority to capture arbitrage, liquidate positions and rebalance liquidity on an orderbook with little risk of adverse selection. This makes it harder for an open market of market makers to compete on an equal playing field as the vault is given structural advantages. But as mentioned early, it might all be worth it - by automating vaults that accept open deposits, the total pool of capital that can market make profitably increases as unsophisticated participants can now deposit comfortably.

Falling Short with App-layer Validity Conditions

In response to the limitations of yesterday’s smart contracts, a number of alternative solutions at the ‘app layer’ have been proposed. While these solutions avoid introducing a new consensus instance, they do look quite like block validity conditions. This is because they involve some combination of verifying conditions were met before execution is settled and pushing computation off of smart contracts. Instances of app layer condition verification + out-of-smart contract computation has gone by many names (e.g., intents, based rollups, Uniswap v4 hooks, restaking, protocol enforced proposer commitments, co-processing). Unlike block validity conditions however, without a separate consensus instance, these app layer solutions fail to give per-block guarantees and can restrict atomicity in some instances. This inhibits their usability and efficiency.

Consider a smart contract DEX on a generalized blockchain which tries to replicate the functionality of a block validity condition. The best this smart contract can do is guarantee that execution will only happen if conditions are met, but it can’t guarantee that they will be met every block. Since not all validators aren opted into these systems, there will be unpredictable delays in execution. And how useful is a DEX which only settle transactions at sporadic intervals ?

As a solution to their usability and efficiency pitfalls, the use of “pre-confirmations” has been suggested. However, pre-confirmations rely on a new set of operators to come to an agreement over the inclusion and ordering of transactions up for execution, which means they require separate consensus (I’ve explored why this is the case in a previous blog if you’re interested in reading more). In the process of introducing a new consensus instance, these pre-confirmation systems end up relying on… programming block validity conditions, it’s just that the trusted validator set is different than the trusted validator set that the verifying smart contract relies on for settlement. These apps can be seen as separate blockchains with expressive bridges to the settlement smart contract.

The Case Against Opinionated Chains

It would be unfair of me to present Opinionated Chains as the end-all-be-all without presenting an alternative future without them.

Enshrining additional block validity conditions are just one solution for getting greater assurances that critical functions will happen within a sensitive time period. In a world where a generalized smart contract chain has :

Sufficiently strong short-term censorship resistance to the point where a block proposer is unable to censor a transaction → inclusion guarantees are virtually per-block

Abundant blockspace to the point where congestion doesn’t price out transactions from landing → low costs to the point where socializing critical functionality is irrelevant

, then almost anything that can be done with block validity conditions should be able to be done with a well designed smart contract. Smart contracts could queue up transactions and have a keeper system to trigger all the “opinionated” functionality in the same or following block.

While in the short-term, no blockchain meets these properties, over a longer time horizon, it’s quite possible these conditions could be met. Innovation in censorship resistance and scalability is pushing aggressively forward.

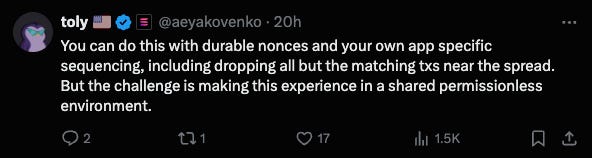

The caveat for “almost anything” is that atomicity becomes much less practical. Ensuring atomicity requires that users can make conditional statements which revert all execution if they are not met. Transactions must be batched together and executed alongside each-other to ensure that any validity conditions (e.g., ordering or inclusion guarantees) are met with respect to the set of them. If it turns out that a transaction desiring atomicity, made a conditional statement that is not met after the initial batch execution, the entire batch of transactions would need to be reverted and re-executed without that transaction since it’s failure would affect their output. This process of restarting is costly and can’t be predicted ahead of time without trial and error - batches must be simulated in full with a process for dropping reverting transactions until a valid sequence is found. At best, handling this on-chain is extremely complicated and costly. At worst, handling this on-chain is impossible. This is likely what Toly means by ‘the challenge is making this experience in a shared permissionless environment’.

One solution to this concern would be to build clusters of smart contract-based applications that share cluster-wide validity conditions. Atomicity could be guaranteed within this cluster but not between this cluster and outside contracts. However, it’s likely that the complexity of building such a framework isn’t worth it. Giving up atomicity with other applications on a generalized chain defeats much of the benefit of colocating with existing apps on that platform in the first place.

Alternatively, it could turn out that atomicity is not as important as I’m assuming it is. Appchain ecosystems could reemerge as contenders by iterating on their outstanding shortfalls. Even if they can’t achieve cross-domain atomicity, shrinking block-times would improve their ability to compose time-sensitive transactions across multiple app(chain)s. Appchains are also expensive - appchains warrant smaller speculative valuations (priced closer to apps than platforms) but still need to pay for dozens of validators with illiquid tokens. Approllup ecosystems remove some of these costs, while retaining full customizability for appchain developers (e.g., Initia’s interwoven stack). It’s also reasonable to say that many of the largest roadblocks for appchain ecosystems were not technical, but social. Ongoing leadership changes could prove valuable in solving these problems (as in the case of Cosmos’ ICF) or entirely new incumbents with fresh perspectives (as in the case of Initia). But since I weight the value of atomicity to efficiency and the simplicity of synchronous composability for developers pretty highly, I would expect that the more realistic outcome is that appchains will make a resurgence primarily for applications which can thrive in isolation.

Perhaps the most likely outcome that could undermine the rise of opinionated chains are generalized rules which are superior to appspecific ones. One promising direction is giving strong guarantees for chain-wide, first-in-first-out (FIFO) ordering. One way to think about FIFO is that it is a latency minimizing and censorship resistance maximizing ordering rule - if I submit a transaction it is included right away. Proponents of FIFO ordering argue that open competition at low-latencies is essential to maximizing liquidity depth. While this is how most public markets work in traditional finance, it is impossible to do reliably with today’s consensus algorithms. That said, researchers have been working on this problem for some time now, so it is quite possible solutions do emerge. In the meantime, we’ll likely see most FIFO proponents pursue single-sequencer designs that allow them to sequence transactions without the costs of decentralization.

Conclusion

Opinionated blockchains are emerging as an attractive middle-ground which merges the willingness of appchains to enshrine opinionated block validity conditions and the more seamless developer and user experiences that generalized chains have. Many teams are moving more and more towards this direction including Hyperliquid, DYDX, Neutron and more.

It also turns out that many of the promising ‘app layer’ solutions to critical problems can be seen through the lens of imperfectly replicating what block validity conditions provide builders (with the added benefit of not needing to build an entirely new consensus process). However due to their limitations, it is likely that even generalized chains begin to make more opinionated decisions by enshrining block validity that assist in their goals.